The Book of Jonah recounts the story of a prophet commanded by God to deliver a message of repentance to Nineveh—an enemy city regarded as the epicenter of wickedness in its time, situated in what is now northern Iraq.

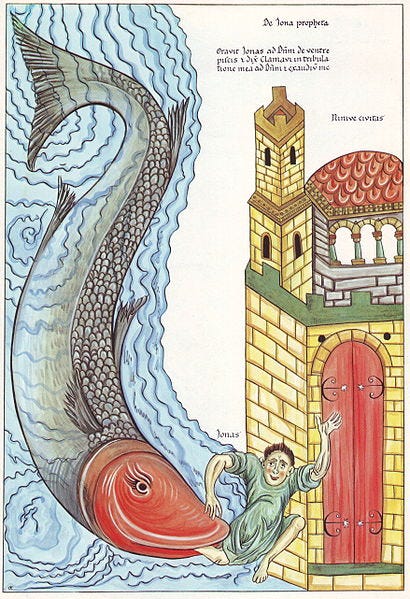

Instead of obeying, Jonah tries to escape his mission by boarding a ship in the opposite direction. A violent storm erupts, and Jonah, realizing he is the cause, is cast overboard and swallowed by a great fish. After three days, he is spat out onto dry land. Only then does he finally journey to Nineveh and deliver God’s warning.

Remarkably, the people of Nineveh—including their livestock—repent. God forgives the city, but instead of rejoicing, Jonah sulks beneath a withered plant, bewildered by divine mercy. The standard moral is clear: no one can outrun their responsibilities; repentance is always possible, and God’s compassion extends even to those we might consider undeserving.

Yet, on Yom Kippur—the holiest day of the Jewish year—this story is read not as solemn instruction but as cosmic comedy. Jonah’s every action is a study in avoidance and petulance: he flees from God, naps through a deadly storm, and delivers what may be history’s least enthusiastic sermon. The people of Nineveh, and even their cows, outdo Jonah in piety, donning sackcloth and fasting with a zeal that borders on slapstick.

The supposed hero is the only one who never really gets the joke.

On the day of ultimate soul-searching, Jews are confronted not with a paragon of virtue but with a parody of prophetic dignity—a reminder that nothing is more absurd than running from the truth, except perhaps taking oneself too seriously while doing so.

Jonah’s story is a mirror for anyone who has ever dodged a difficult truth or responsibility. The impulse to “run away”—from a tough conversation, a looming obligation, or an uncomfortable self-reckoning—is universal. Yet, as Jonah’s misadventures show, avoidance rarely brings peace; it often amplifies the problem, dragging others into the storm and leading to greater discomfort before resolution is possible.

The Book of Jonah is also a critique of national self-righteousness and the refusal to see the humanity in one’s enemies. For ancient Israel, Nineveh embodied existential threat and moral depravity—yet the story insists that even such an adversary is not beyond the reach of compassion and repentance.

For modern Israel, the temptation to view Gaza or Iran solely through the lens of threat and enmity echoes Jonah’s original prejudice. This is not a call to ignore danger but a challenge to the presumption that reconciliation is impossible and that mercy is weakness.

Jonah’s failure is not only personal but national: a refusal to imagine that “the other side” might change or that one’s own side might need to repent as well. The story warns against the self-destructive consequences of denying the possibility of change—whether in oneself, in one’s enemies, or in the world at large.

Today, Israel often subordinates Palestinian suffering to its own story and tends to frame all resistance as Iranian proxies. These are forms of self-deception that echo the biblical story of Jonah, perpetuating conflict and undermining Jewish moral tradition.

True strength means confronting the root causes of violence, including occupation, dispossession, and inequality. Real progress comes from addressing these issues head-on, not from doubling down on force or ignoring one’s own complicity.

Commentator and former Zionist Peter Beinart warns that clinging to innocence while ignoring suffering in Gaza and elsewhere is a dangerous evasion of responsibility—one that ultimately makes Israelis less safe and erodes the moral foundations of Jewish identity. His view is shared across the political spectrum and by a growing majority of Americans, who increasingly demand a more just, humane, and accountable approach—not only to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but also to U.S. policy toward Iran and American power in the region.

The U.S. and Israel’s pretensions about regional dominance are more about power than security; their strategies go far beyond defensive needs and are fundamentally about maintaining and expanding influence, control, and leverage in the Middle East—and, as critics have noted, they distract from executive scandals or legal challenges at home.

In its comic wisdom, the Book of Jonah leaves us with a counterintuitive truth: sometimes, the only thing more dangerous than your enemy is your certainty that you’re nothing like them.

The religious vision is not about seeing things that are not there; it is about seeing the things that are there and always were—often easier to ignore.

Notes and reading

Hebrew Bible, Book of Jonah (Chapters 1–4)

Talmud, Mishnah Yoma 6:2. (Jonah read on Yom Kippur afternoon)

The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary - Robert Alter (2018); Jonah: A New Translation with Introduction, Commentary, and Interpretation - Jack M. Sasson (1990).

Jewish tradition: Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, “The Unasked Question” (2014). Posted on the Rabbi Sacks Legacy site, it has become a key reference in contemporary Jewish study and debate. Sacks addresses Jonah’s reluctance, God’s mercy, and the interplay between justice and compassion.

Sacks—an Orthodox rabbi, philosopher, and theologian—served for more than twenty years as Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, the UK’s senior rabbinic post.

Peter Beinart – His book, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning, has set off a storm of argument in the American Jewish world and well beyond it. Plenty of readers bristle at his criticism of Israel and Zionism. A growing crowd sees their own doubts echoed in his pages and is rethinking its relationship with Israel and where the country is headed.

Will Iran now accelerate its efforts to build the bomb, as the only guarantor of its safety?

Tip-Off #213 - Written in Stone: Broken at Birth

Time-Out - Chaos 2.0

I love how you frame the war in Gaza with the Yom Kippur reading of Jonah. The "comic wisdom" you highlight from the book makes me reformulate a reading from the Gospels: no path to lasting peace and to moral suasion exists except for the path of the prophet Jonah.

Thank you for introducing me to Beinart's book. I can't wait to read it.