Personal note: Why another post so soon? Blame political argument—and a rediscovered box of Midrash buried under coats and cables. Centuries of commentary, just waiting to be dusted off.

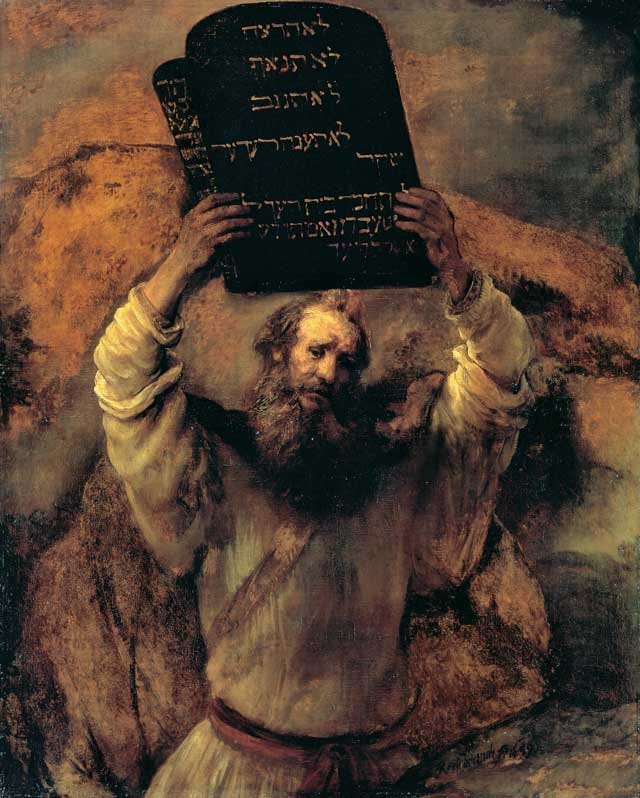

The Ten Commandments often get hauled out like moral traffic lights stuck on red—mostly to scold other people. In some circles, they’ve become less a moral guide than a blunt weapon, waved at school boards, courtrooms, and godless liberals. Biblical law turns into a holy citation pad: Thou Shalt Not, full stop. Nuance evaporates. Yet the very texts being weaponized are more complex and humane than their loudest champions admit.

Biblical law itself emerged within the concrete realities of the ancient Near East. It was never written for abstract ethical debate or modern litigation; it spoke to fragile kin-based villages. Rather than laying down universal principles, its statutes read like case studies: what if an ox gores a neighbor, or someone moves a boundary stone? The aim was responsibility and repair, not retribution. Without formal courts, enforcement was often handled through family, clan, and ritual.

Some provisions echo Mesopotamian and Egyptian codes—rules that seek fairness, limit power, and define social roles—yet Israel roots those concerns in covenant, a relationship between God and people marked by mutual commitment and shared responsibility. Regulation becomes relationship; the giving of law is itself an act of care.

These texts do not hand us ready-made policy. Their gift is gratitude and recognition: gratitude for deliverance from bondage, and recognition of how a community organized life under divine expectation—how accountability took shape in a world removed from ours.

When Moses descended from Sinai with the tablets, he expected devotion and found chaos—a golden calf, frantic dancing, trust undone. In anger, he shattered the stones God had just given him. God then told him to carve another set. Those new tablets went into the Ark of the Covenant—but so did the broken shards. As the Talmud notes, “Both the whole tablets and the broken tablets lay in the Ark” (Berakhot 8b). Israel carried both through the wilderness: success and failure side by side.

We like to showcase the flawless version of ourselves. The Ark insists otherwise: brokenness is not discarded. Early ideals, dashed hopes, mistakes—they all remain part of the sacred narrative. Truth never excludes the human story.

A Midrash—a traditional Jewish interpretive story—deepens the point. In Shemot Rabbah 5:9, we read, “The voice of the Lord split into seventy languages.” Every word of Sinai resounded in all tongues, signaling that the teaching was meant for every nation, not Israel alone.

Perhaps that is the hidden commandment: carry it all—whole and broken—and let the words reverberate far beyond the desert. Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” distills the point:

Ah, the wars will be fought again,

the holy dove will be caught again—

bought and sold and bought again;

the dove is never free.Ring the bells that still can ring,

Forget your perfect offering;

There’s a crack in everything—

That’s how the light gets in.

Cohen grasped how violence repeats whenever perfect offerings replace honest confession, yet he still urged listeners to ring imperfect bells.

The tablets of biblical law themselves echo that plea. Stone endures, but Torah expects interpretation: prophets, rabbinic debate, and modern scholarship all prod the community to reread and renew the covenant.

"God is still speaking." Law, in other words, is living argument. Treating it as a frozen manifesto betrays its lifeblood. Even the biblical text records revisions, contradictions, and expansions, showing that revelation invites response, not passive recitation.

That insight reaches far beyond jurisprudence. Families mend after betrayal, cities rebuild after war, and democracies survive only when they admit failure and adjust. Carrying the broken shards is not a burden; it is the design. Where fracture is acknowledged, hope can circulate; where it is denied, darkness congeals.

Echoing Cohen’s reminder that light streams through fractures, Peter Beinart today warns that Israel’s hard-edged nationalism—from Gaza to escalating threats against Iran—reveals fissures no army can seal. Only an unflinching reckoning, joined to justice that safeguards the sovereignty of Israel’s adversaries, can redirect those cracks into channels of light instead of fault lines primed to rupture the region.

Those who wield the Commandments as fixed signals—red for others, green for themselves—miss the deeper ethic at the heart of biblical law: not domination, but accountability; not purity, but repair. Invoking covenant—a relationship of trust and responsibility—while refusing to carry both whole and broken betrays the very story they claim to defend.

In times like these, clinging to a narrow, punitive reading of scripture does not uphold righteousness; it disfigures it. The Commandments were never meant to sanctify power. They exist to humble it—in the capitals of the world, and among the angry moralists at home.

Even our Liberty Bell has a crack.

Notes and reading

“When so much of the world is plunged in darkness.” – Leonard Cohen, Anthem Official Live in London 2008.

Midrash – Part of the oral Torah: “It was inconceivable that the sense of the Torah of God conflict with the fundamental conditions of Jewish life. The written letters of the Holy Writ were not meant to kill the spirit. They were intended as containers ever to be filled with the wine of good, new vintage.” – Foreword, Midrash Rabbah (The Soncino Press, 1983).

As one Midrash (Sifre Devarim 49) says: “Every day, the words of Torah should be new in your eyes.” Midrash isn’t just what was said—it’s what can be said when sacred text meets curiosity and dialogue. In reading this post, you and I are—midrashically—taking part.

I considered writing “we.” But that would only blunt the edge. Tradition doesn’t happen in the abstract. It lives—or fades—through encounters like this.

“God is still speaking” - the motto of the United Church of Christ (the Protestant denomination to which I belong).

A Theology of the Old Testament: Cultural Memory, Communication, and Being Human – John W. Rogerson (2010). Celebrated for his intellectual range and rigor, Rogerson (d. 2018) bridged fields from anthropology to biblical interpretation—and earned lasting respect for his mentorship and integrity.

Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning – Peter Beinart (January 2025). Once a leading American defender of Israel, Beinart has since rejected core tenets of Zionism—from the idea that Israel can be both Jewish and democratic to supporting the right of return for Palestinian refugees. He advocates a Jewish tradition grounded in equality, not supremacy. A professor at CUNY, he formerly edited The New Republic and now contributes to Jewish Currents and The New York Times.

“New Texas law requires 10 Commandments to be posted in every public school classroom” – Politico (June 21, 2025).

Time-Out — Chaos 2.0

Tip-Off #212 — Fear and Hospitality

Oh, this is so good: "Law . . . is living argument. Treating it as a frozen manifesto betrays its lifeblood. Even the biblical text records revisions, contradictions, and expansions, showing that revelation invites response, not passive recitation."

It's all a wonderful reflection on the Ten Commandments in the context of Israel's history as well as of our current fetish over it as a rock of absolutism in a sea of relativism. As your post suggests, community in the form of sacred text, tradition, and interpretation is the answer to both absolutism and relativism as well as to the nihilism that follows them both.