Tip-Off #212 - Fear and Hospitality

"Hospitality is culture itself and not simply one ethic amongst others." — Jacques Derrida, "On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness."

The politics of immigration flounders without a culture of immigration. But in today’s hyperpolitical atmosphere, “culture” sounds like a street fair—colorful, harmless—or, worse, like something coastal elites talk about when avoiding hard realities. Culture doesn’t register next to dislocation, low-wage labor, or the fraught question of who belongs where.

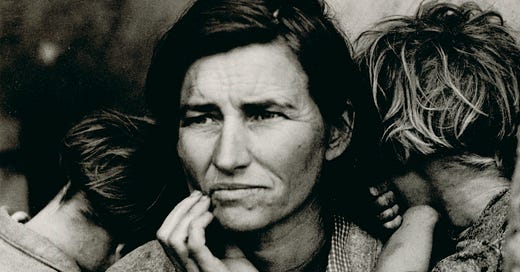

In the absence of such a culture, fear of the stranger fills the void. It feels timeless—a natural reflex. It's most visible in the MAGA movement, where Donald Trump has turned it into his ace: a political strategy that defines his appeal and reshaped public conversation.

Cultures of fear, humiliation, and hope are reshaping the world: fear against hope, hope against humiliation, humiliation leading to sheer irrationality. Fear strikes when people are caught in the middle of a contradiction they can't name. They might long for rootedness in a world of mobility or stability in a society that prizes disruption. What gets framed as xenophobia is often a misfired response to disorientation. The stranger becomes a stand-in for something more intimate: the loss of place, identity, or control.

The modern, politically charged fear of the foreigner is a recent invention, not an ancient curse. Its antidote, hospitality, is a practical, buildable framework, not just a personal virtue. Unmasking the origins of this fear reveals a blueprint for a more welcoming world.

Psychiatrist-historian George Makari traces how xenophobia—a word coined amid the late-nineteenth-century swirl of nationalism, empire, and mass migration—pathologized those resisting colonial rule. During the anticolonial Boxer Rebellion, Chinese patriots were labeled not defenders of their homeland but patients gripped by an irrational dread of foreigners. Invading powers cast themselves as benevolent; those who opposed them were said to suffer a cultural disorder. By projecting the terror they provoked onto their victims, the aggressors could brand dissent as pathology—and dismiss it. “Xenophobia” originally had less to do with a fear of strangers than with their fear of us.

History reminds us that fear is cultivated—so it can be dismantled. The remedy lies less in politics than in the everyday art of welcome. Hospitality cannot be legislated, yet it can be nourished—locally and culturally, without waiting for Washington. Policy works best when it resonates in neighborhoods and reflects our own sense of self.

Sociologist Irene Bloemraad offers a roadmap. Her comparative research shows that immigrants are more likely to naturalize and engage in civic life—and enjoy acceptance—when communities actively encourage a sense of belonging. That can mean language classes in churches, soccer leagues in school gyms, or open mics at town halls. Such venues let neighbors discover that what they fear in others often reflects what is unsettled in themselves. Before others are strangers to us, we are strangers to ourselves.

Princeton physicist Peter Putnam called this the mind’s “logic of contradiction”: we make sense of the world inductively—by dealing with tension first, then testing patterns and revising beliefs. Recognizing our own inner knots is the first step toward meeting the contradictions others carry.

Coalitions for inclusion are built not on sentimentality but on an enlarged perspective, sometimes described as “the spatiality of thought,” and on shared values: work, family, faith, and reciprocity. Hospitality is not a sporadic kindness; it is, in philosopher Jacques Derrida’s words, “culture itself”—the question by which a society defines who it is and how its members will live together.

Consider a small example: Front Porch Republic (FPR) is an online forum devoted to localism and communal life. It began with a diverse group of writers across the political spectrum concerned that centralized power and social fragmentation were eroding genuine community. The site explores both historical patterns and present-day challenges—including immigration—in terms of place, tradition, and civic responsibility.

The spirit of that forum is as replicable as a neighborhood email. I sent one—back when email still felt novel: "Pray for Peace—anyway.” Mondays, 7 p.m., 2515 Kemper Rd. People showed up, bemused but intrigued—immigrants and lifelong locals, strangers and friends from different races and backgrounds, even a Zoroastrian who had escaped from Iran and, problematically, several missionaries.

The meetings were sometimes dull, sometimes heated—mostly bracing. No plaintive flute played in the background.

Stories like this aren’t rare—we could all tell them. Meanwhile, the rest of the world settles for more Trump talk.

The deeper work isn't in headlines but in neighborhoods, where contradiction meets recognition—and welcome begins.

Notes and reading

Hospitality as Culture—Jacques Derrida, On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness (2001). Derrida roots his claim that “hospitality is culture itself” in the Bible’s “cities of refuge” for resident aliens. The phrase “spatiality of thought” is from philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space.

Understanding through Contradiction—Amanda Gefter, “Finding Peter Putnam: The Most Brilliant Man You’ve Never Heard Of,” Nautilus, June 17, 2025. “Jazz is the mathematization of the soul.”

Working nights as a janitor, Princeton physicist and former Union Theological Seminary professor Peter Putnam—admired by Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, and once a teacher of my brother David, then a seminary student—developed an unpublished “logic of the mind.”

Putnam argued that humans reason inductively—by confronting contradictions, testing patterns, and revising beliefs. While he didn’t address AI directly, his model contrasts with how rule-based AI systems operate today: deductively, from fixed premises, in a logic that is exponentially axiomatic.A History of Xenophobia—George Makari, Of Fear and Strangers: A History of Xenophobia (2021). In a globalized world, fear plays an increasingly significant role in determining who gets to belong. Renowned in both psychiatry and history, Makari approaches xenophobia with notable authority.

Emotion and Power—Dominique Moisi, The Geopolitics of Emotion (2009). Moisi maps how cultures organized around fear, humiliation, or hope channel those emotions into politics, law, and identity.

The Geometry of Fear—Research links fractal patterns in brainwaves and heart rhythms to fear’s recursive nature. Recognizing these patterns, like spotting an undertow, helps us resist their pull. For a vivid and popular take, see Badhan Sen’s “The Emotions of Fractals” (Vocal Media, April 2025), which explores how self-similarity in emotions reveals hidden order beneath chaos.

Citizenship in Practice--Irene Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen (2006), compares how the U.S. and Canada incorporate immigrants and refugees—key for understanding multicultural policy.

A Liturgy - for protesting with strangers—Bryce Tolpen, Political Devotions, Substack (April 10, 2025). "Inspired by Thomas Merton & our three-person D.C. protest."

Tip-Off #211 - Sore Truth

Tip-Off #210 - Dancing on Quicksand

I naturally noted your own Substack, "Political Devotions" in the endnotes. - You lend your own emphasis to some of these points in ways I always find thought-provoking. So thanks in turn!

This is a great dialogue, also a good reading list. Thanks.

My mentor Letty Russell’s last book’s title, Just Hospitality, speaks at once to humility of practice and a deep sense of justice and how it works.

https://a.co/d/68cze5Q