Thanksgiving, anyway

Love in the void.

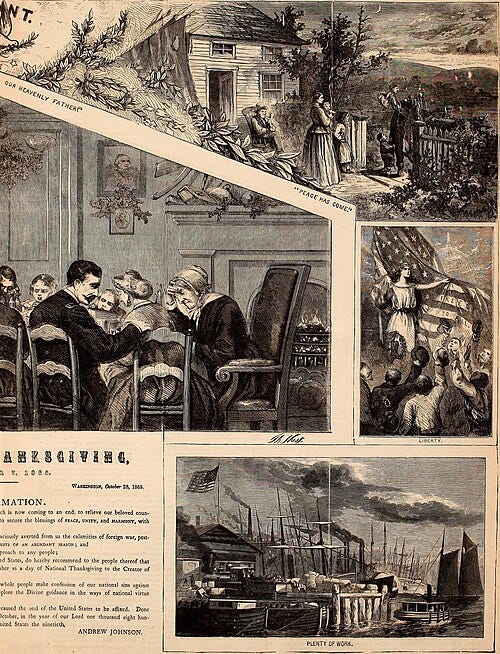

The first Thanksgiving celebration is traditionally dated to 1621 in Plymouth, Massachusetts—but it came on the heels of catastrophe. Arriving in November 1620, too late to plant crops, the Pilgrims were utterly unprepared for the brutal New England winter. Roughly half died from disease, malnutrition, and exposure.

Their survival depended on the Wampanoag people: Squanto taught them to cultivate corn and fish; Samoset made first contact; and Chief Massasoit established a peace treaty. The 1621 harvest feast celebrated survival against terrible odds—a moment of relief and gratitude after profound loss.

This context is often overlooked in simplified Thanksgiving narratives. It makes the moment more poignant and complex, given the subsequent tragic history between European colonists and Native Americans.

This is the setting of gratitude in the Bible. The book of Lamentations mourns Jerusalem’s destruction, yet offers this famous passage: “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.” Despair holds the promise of deliverance.

One thing I keep coming back to when reading the Bible is how often we project our own sense of hope and promise, right and wrong, onto God—and then wonder why God refuses to play by our rules.

There’s a deep impulse in religion to shape the world into something bearable, to imagine a God who fits that world, and then bow down before that creation. The Bible doesn’t cooperate. It keeps refusing to let us domesticate God.

What emerges from Scripture isn’t a way to keep divine presence close. It’s a long, slow education in letting go. Revelation is real, but never on demand. God shows up—powerfully, unexpectedly—then disappears. Over and over.

Divine nearness flares up in burning bushes, temple glory, visions, and healings. But every time people try to lock that presence into a place or system—a tent, a temple, a law, a king—it slips away. The ark is captured. The temple burns. Prophets thrive on doom.

The Bible offers us rituals, doctrine, covenant—but then tells us those are never the whole thing. “The Most High does not dwell in houses made by human hands” (Acts 7:48). Even the holiest things become obstacles when we mistake them for the presence itself.

The golden calf moment captures this perfectly. Fresh out of slavery, the people grow restless while Moses is up the mountain. So they melt their gold and shape it into a calf. They aren’t worshiping a different god—they’re trying to pin down the real one. They want something they can carry, see, and manage. And they get rebuked not because they’re irreligious, but because they’re trying to make God graspable.

In a later story, Naaman the Syrian, a foreign military commander seeking healing from the prophet Elisha, expects a spectacle. Instead, he’s told to wash in an ordinary river. He nearly walks away. But the healing comes not in the show he hoped for, but in the disappointment.

That pattern runs through the Gospels. Jesus speaks in riddles, slips through crowds, and turns power upside down. He says the Spirit moves like wind — unpredictable, uncontrollable. He teaches how to live with absence: poor in spirit, watchful, merciful, interruptible.

There’s something oddly consoling about this. Maybe even freeing.

Religious certainty can go sideways fast. When we think we have God boxed in, we get defensive, rigid, or cruel. The belief that we’ve nailed down the truth often licenses violence.

Jacques Derrida (yes, that Derrida) might call this theological non-closure—a refusal to let meaning, or God, be finalized. It’s not a denial of truth; it’s a resistance to idolizing our own grasp of it.

But if God is free and won’t be pinned down, we’re forced into a different posture. Less clutching. More receiving. Forgetful as we are of the past’s wisdom, we still associate gratitude with thoughtfulness and memory. “Thank” and “think” share the same root.

When prayer feels dry, when institutions disappoint, when God seems absent, this pattern in Scripture reminds us: absence is not just failure. It’s part of the path.

The Bible expects a God who comes and goes. We’re not promised clarity. We’re promised that the one who eludes our grip still seeks our good.

We can’t receive a gift when our hands are full. The empty hands left by absence are open to receive. Ironically, the Pilgrims’ survival—which we celebrate as the first Thanksgiving—depended on help from the very people whose land and lives would later be taken.

More ironically still, a Native American tradition may best capture the wisdom the Pilgrims needed: the Haudenosaunee “Thanksgiving Address” expresses gratitude for each element of creation—not despite suffering, but acknowledging that life and death, presence and absence, are inseparable parts of the same reality.

Etho niyohtónha’k ne onkwa’nikón:ra ( “Now our minds are one.”)

Notes and reading

Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address

Bible verses

Acts 7:48 NRSV. In the First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament: “the One Above Us All does not live in lodges built by human hands.”

Exodus 32:1–35, the golden calf episode at Mount Sinai.

2 Kings 5:1–14, the story of Naaman’s healing.

The Elusive Presence: Toward a New Biblical Theology—Samuel Terrien (1978). Terrien was a leading biblical scholar who taught at Union Theological Seminary in New York for 35 years.

The Silence of Jesus—James Breech (1983). Breech was a professor of biblical studies at York University in Toronto, Canada. “As T.S. Eliot observed, ‘human kind/ Cannot bear very much reality.’ The spirit of Jesus is a passion for the actual.”

Derrida and Negative Theology, ed. Harold Coward and Toby Foshay (1992), especially “How to Avoid Speaking: Denials.” Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance—the perpetual deferral of final meaning—parallels apophatic (negative) theology’s refusal to fix God within human categories.

Wampanoag Tribe—For the Wampanoag people, Thanksgiving is deeply complex: their ancestors held four harvest festivals throughout the year to give thanks for the earth, the seasons, and their blessings. Yet the modern holiday also serves as a painful reminder of the colonization that followed the 1621 encounter with the Pilgrims. Many Wampanoag, along with other Native Americans, observe Thanksgiving as a day to remember their whole history, the tragedy, and the resilience. (For background on Wampanoag perspectives on Thanksgiving, see “Native Americans Share Long-Ignored Thanksgiving Truths,” Al Jazeera, November 25, 2021.)

This Thanksgiving essay doesn't serve up the traditional meal of holiday platitudes. It shows how we can give thanks consistent with a God who won't be reduced to our expectations and conceptions--and consistent with the traditions of thanksgiving maintained by the Wampanoag and the Haudenosaunee before and after the "original" Thanksgiving centuries ago. The essay is the first to show me that we don't have to choose between what has become a traditional Thanksgiving, often insensitive to its historical lessons, and (pardon this) going cold turkey.

I love how this essay starts with Thanksgiving, weaves away from it, and returns to it in force: “‘Thank’ and ‘think’ share the same root.”

Some of my favorite lines:

“What emerges from Scripture isn’t a way to keep divine presence close. It’s a long, slow education in letting go.”

“Jacques Derrida (yes, that Derrida) might call this theological non-closure—a refusal to let meaning, or God, be finalized. It’s not a denial of truth; it’s a resistance to idolizing our own grasp of it.”

Thank you for this reflection as well as for your reference to James Breech's The Silence of Jesus. I read its introduction online and was intrigued, so I ordered a copy.