Room for Love

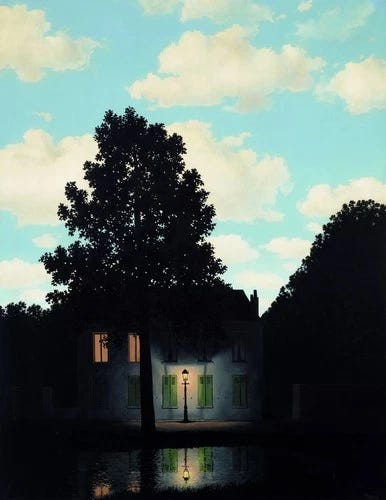

“In the darkness of our lives, there is not one place for Beauty. The whole place is for Beauty." - René Char, Hypnos

Advent begins with a question that reaches well beyond religious boundaries: how love arrives without force, possession, or control. The four Sundays of Advent prepare for the Incarnation—the claim that God became fully human in Jesus Christ, the long-debated and often misunderstood center of the Christian story. It is a season of waiting, a moment when the world seems to hold its breath.

Jesus is not “God” in any thin or simplistic sense. Christians have argued about that from the start. What the tradition insists on—often badly, sometimes well—is that in Jesus the life of God is fully disclosed within a human life. As the carol puts it, “It came upon a midnight clear”—light breaking into shadow. Nothing human is canceled or bypassed; it is taken up, transfigured, and drawn toward what it was always meant to become.

Love does not bypass our limits; it inhabits them—and they stretch.

The Incarnation does not introduce something new so much as make visible what has been present all along: salvation as the gradual clarification of love.

In this sense, love is not first a feeling or an achievement but the animating force of life itself, already at work before we notice it. Divine love is non-possessive and non-coercive. It does not erase difference or force likeness but delights in the reality of the other. It desires without grasping and gives without reducing what it loves. The Incarnation, then, is not an interruption in the world’s story but its disclosure—the unveiling of a love that sustains creation by allowing nearness without collapse and communion without control.

Advent invites a different way of thinking about love—not a love divided into parts, self-giving here, desire there, friendship somewhere else, but a single movement that holds these together. It draws near without collapsing distance. It seeks the other's good without attempting to secure it in advance. It delights in presence without mistaking closeness for possession.

Advent draws us into patience rather than control. Love does not announce itself with certainty or arrive by force. It asks only for room—room for freedom, surprise, and change. To wait in this way is not passive but attentive: a readiness to receive what we did not plan. Love is not weaker because it refrains. It is truer because it allows what it loves to remain other.

By contrast, our own efforts to love feel familiar and complicated. For centuries, marriage functioned primarily as a means of survival—preserving property, continuing family lines, and meeting social expectations. Love and affection could follow, but personal compatibility mattered less. Romance was welcome, not required.

Today, love is often framed as finding someone who meets our requirements. It becomes something we manage rather than something we grow into together. Social critics—not only religious ones—argue that an emphasis on choice and control turns relationships into fungible goods, optimized and replaced.

Dating apps intensify this logic, packaging some of the most human experiences for consumption. In a culture devoted to hacks, routines, and self-improvement, even Jesus is marketed—personalized holograms today, perhaps pocket versions tomorrow.

The cultural critic Byung-Chul Han describes our condition as an “inferno of the same,” where even difference reproduces what we already know. We follow the rules of nonconformity. Novelty wins by default. Failure is not allowed.

So much for friendship.

Han suggests that partnership requires a certain kind of failure—a resistance to mastery. The problem is not that we want to possess others but that we want to understand them so completely, on familiar terms, that nothing remains strange or resistant. If that were possible, they would no longer be someone else but versions of ourselves.

Mystics have long resisted this impulse. Meister Eckhart insisted that “God is greater than God,” meaning that whatever we manage to grasp is already too small. Rilke described love as “two solitudes that protect, touch, and greet each other.” Both understood that closeness needs space to breathe.

Intimacy thrives in paradox. It requires both nearness and distance. This tension runs through many love stories. Anna Karenina’s affair with Vronsky promises total union, yet the intensity that draws them together also pulls them apart. When love tries to erase boundaries, it ends by consuming itself.

Advent offers another possibility. As love draws near, it does so without force. It does not depend on guarantees or control, but on a readiness to receive what comes without reshaping it to our expectations. Nearness and distance are not opposites to overcome, but gifts to be held together.

What follows below stands within that same threshold. Heard late in Advent, this music inhabits the space between waiting and arrival. [*] 3:35

This is the delight of a love that comes very close without overwhelming—and in doing so, changes how we learn to love others.

[*] J.S. BACH: Little Fugue in G minor, BWV 578. Paul Jacobs, organ; the Hazel Wright Organ, Christ Cathedral, Garden Grove, CA. Recorded on one of the world’s largest instruments (nearly 300 ranks and 17,000+ pipes), the internationally acclaimed Jacobs captures the Fugue’s Advent character: it builds with patient intensity, revealing joy as light clarifying within shadow—a strength that holds complexity without force. Cf. Peter Williams, The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2003).

Close-ups of the organ, the organist, and pedalwork. If the embedded link (triple-click) does not play, open YouTube here.

Notes and reading

The four Sundays of Advent are traditionally associated with hope, peace, joy (Gaudete), and love, respectively.

“In the darkness of our lives, there is not one place for Beauty. The whole place is for Beauty.” —René Char, Leaves of Hypnos (Feuillets d’Hypnos), feuillet 237, in Furor & Mystery and Other Writings (2011); paraphrased. Char (1907-1988) was one of France’s most respected 20th-century poets, acclaimed by Martin Heidegger and other notables.

Denis de Rougemont—Love in the Western World (1940, 1983). A seminal survey arguing that Western romance is historically rooted in heresy and inherently opposed to the stability of daily life. Love Declared: Essays on the Myths of Love (1963). A companion volume that shifts focus to the “crisis of the modern couple,” offering a more constructive vision for how love might survive the myths that threaten it.

Byung-Chul Han—The Transparency Society (2015). Han denounces transparency as a false ideal, the strongest and most pernicious of our contemporary mythologies. Han is a South Korean-born philosopher and cultural theorist living in Germany.

David Bentley Hart—The Beauty of the Infinite: The Aesthetics of Christian Truth (2003), esp. chs. 3–4. Hart argues against dividing love into competing forms (agapē, erōs, philia). Divine love, he maintains, is a single movement that desires, gives, and delights in the irreducible otherness of the beloved, drawing creation toward communion—and into participation in God’s own life—without coercion or possession.

Stephen A. Mitchell—Can Love Last? The Fate of Romance Over Time (2002). A modern classic of psychoanalytic theory that challenges the assumption that passion must fade with familiarity. Cf. Esther Perel—Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence (2007). A controversial bestseller examining how modern ideals of closeness and equality complicate sexual desire.

This essay is strong testimony along our pilgrimage to Bethlehem. So many good things to talk about:

The Incarnation makes visible “salvation as the gradual clarification of love.” This realization gets at it so nicely.

Love as life’s animation. Yes! The rocks and stones cry out in love. Augustine speaks with the earth and its creeping things, the sky and its birds, the heavens and their planets and hears from them that they are not his God. Marshall Sahlins recounts Augustine’s conversations and playfully (?) calls him a “pure animist.”

The Incarnation as “the unveiling of a love that sustains creation by allowing nearness without collapse and communion without control.” What a wonderful description of love’s private and public lives.

And this is a beautiful invitation into Advent’s dynamic: “Advent draws us into patience rather than control. Love does not announce itself with certainty or arrive by force. It asks only for room—room for freedom, surprise, and change. To wait in this way is not passive but attentive: a readiness to receive what we did not plan.”

By the way, I love Char. Arendt’s fascination with a line of his Leaves of Hypnos pointed me to him.