Sam Altman knows me better than I know myself. Algorithms have become best friends—they even tell me how to be original. Em dashes are a giveaway and "authentic" suspect. Better to say "natural." As though we already knew what this meant.

The CEO of OpenAI (ChatGPT), Mr. Altman, is at the forefront of the latest digital technology. Along with peers like Meta's (formerly Facebook's) Mark Zuckerberg and backed by billionaires, Altman is racing toward the Singularity, the moment when machine intelligence surpasses human intelligence, as if this transformation requires some extraordinary leap. Once pegged for 2045, that moment is said to be far closer—2030?

Before long, a device on my wrist could assure you're interested in me. Or ensure that I am actually smart. Even before neural transplants, we are digitalized in competition with various versions of ourselves. We watch the news tailored for us and know what products to buy—which Substacks to avoid and how to be among its top performers. Because all this sounds exaggerated, it will be flagged for exaggeration, inspiring a search for more credible synonyms.

I am taken by advice that the best answer to all this is "to know your own voice." But AI knows that, too, though it takes endless copy editing to make it real. A colleague smirked, saying, "The only way I can be real these days is to be weird." That is already in the data banks, and then AI is blamed for hallucinating.

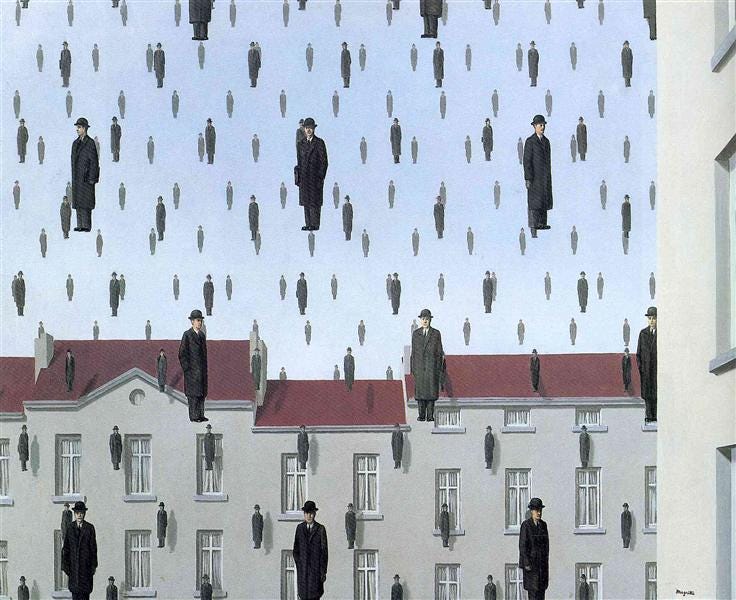

It's easier to stick with our own sound, just as it is. However, in reality, what we consider original is already a copy, a replica of what we assume others want to hear. From birth, our desires are borrowed—shaped by the wants we notice and how they're answered. An infant doesn't just want to be fed; they learn to expect and prefer feeding in the ways they've experienced it. They mimic facial expressions within weeks, orient toward voices, and show preference for familiar tones and faces.

The great philosopher of desire, René Girard, explored the nature of what we want and wrote about "mimetic desire": how we take our cues from others for what is worth wanting. We learn how to be selfish before we find out that's not what others like.

In literature, another thinker spoke of the "anxiety of influence"—the struggle to overcome or creatively misread the work of great predecessors to assure one's own originality. Outside literature, the same dynamic plays out in life: we discover new ambitions when we see them in someone else's hands. I want to write well because many of you, my readers, inspire me to do so, and I don't want to be judged otherwise.

The drama of artificial intelligence makes us think our times are unprecedented. Plato spoke of the advent of writing itself as a threat to the truth. While his own Dialogues are written, and Socrates ended up composing a poem, the argument was that writing would weaken memory and give only the appearance of wisdom, knowledge borrowed from words fixed on a page rather than gained through one's own understanding. Yet, as Plato taught in his doctrine of the soul's preexistence, our understanding is itself "borrowed" and mimetic, and speaking firsthand is no closer to the truth. The critique of writing as derivative points to something deeper: our relationship with language itself is fundamentally imitative.

Originality is already a myth—or what, in another context, Plato called a "noble lie." Every sentence carries someone else's touch. Speech doesn't outrun imitation; it only hides it. AI makes the remix obvious. So the question isn't purity but responsibility: which voices we trust, which desires we refuse, which we choose to pass on. If there's such a thing as originality, it's selection with a conscience.

AI has no conscience except what we program into it. It can be critical, but it cannot wrestle with the deeper question of what ought to be imitated. That wrestling—the conscious choice of which influences to embrace and which to resist—remains distinctly human.

Scripture speaks of disciples as "imitators of Christ.” Who shall we imitate? Christ or something Christlike, a brilliant thinker like Plato, a superhuman machine?

The old gospel song offers one answer: "Just As I Am"—not a rejection of influence, but an acceptance that we are always, in some sense, an original copy, shaped by what we've received and responsible for what we give.

Notes and reading

Cf. Tip-Off #61 – Back to the Future

Cf. Tip-Off #142 – How Love Should Begin

Cf. Tip-Off #209 – Authorship and the Ancient Debate

Cf. “Thick” and “thin” desire in Luke Burgis, Wanting (2021), an introduction to René Girard, and “lightness” and “heaviness” in Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984, 2023)

Cf. Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence (1973, rev. 1997) – strong poets “swerve” from precursors, creatively misreading them to make room for their own voice, a drama of rivalry akin to Burgis’s “thick” desire and Kundera’s “heaviness”

Black Mirror, a British anthology series, premiered in 2011 and moved to Netflix in 2016. Each stand-alone episode delves into the dark, satirical aspects of technology’s influence on society, revealing how media, AI, surveillance, and biotechnology can exacerbate human flaws. The title evokes the black screens of our devices—symbols of both fascination and foreboding.

(Thank you, T.L.)

Cf. About 2 + 2 = 5 — Orwell knew the math.

“For who regards you as superior? What do you have that you did not receive?” You make a great point of what AI can teach us even when we turn down its offers at every turn to reword (and so rethink), which is the derivative nature of our contributions. Our first emphasis each fall in freshman comp was to write like we think and talk. And our second turned out to be like unto it: to deliberately imitate the masters.

This reference provides a comprehensive critique of our dreadful sanity

http://beezone.com/current/mind_as_separate_self.html

Plus the Scapegoat Drama:

http://beezone.com/adida/there_is_a_way_edit.html