Millions of people have scanned their eyeballs to prove they’re human. You, too, could become a “verified human,” identifiable at a moment’s notice.

“Big data will see you now,” declared The Economist in the last issue: “Assessing China’s giant new gamble with digital IDs.” South Korea is following suit. In the U.S., the IRS plans to develop a similar capability, consolidating names, addresses, Social Security numbers, tax filings, and employment histories into a single cloud-based platform.

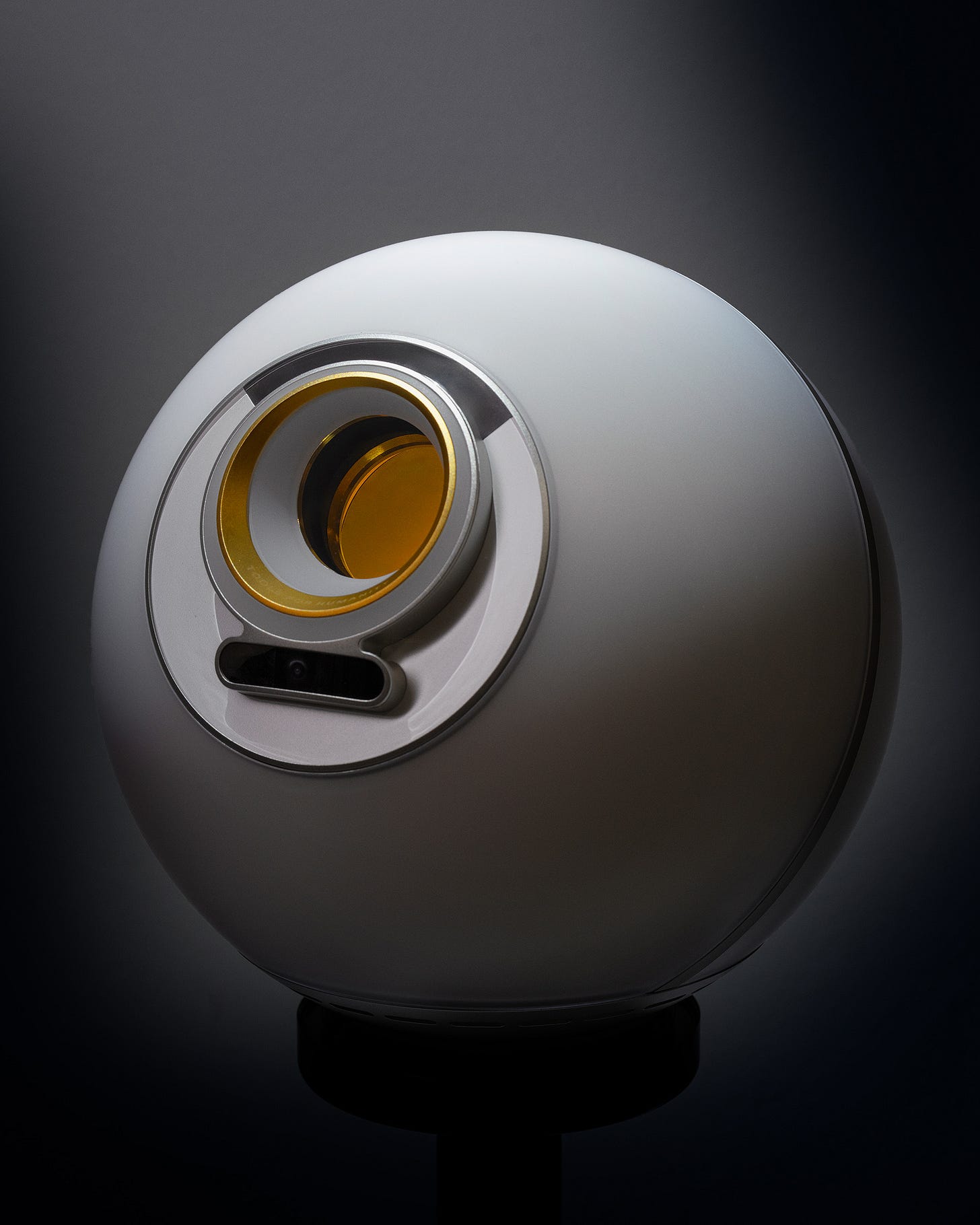

Peter Thiel and Elon Musk are among the prominent investors in AI. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman founded Tools for Humanity to prepare for a future in which the line between human and machine disappears. His answer—the Orb—a biometric device that scans irises to issue a World ID (and a small crypto reward), confirming identity in a digital world crowded with AI agents.

Picture an Orb at every intersection, replacing today's video cameras—supposedly to stop crime and protect national security. ICE could fill its yearly quota in a week.

Altman sees the Orb as infrastructure for the future of artificial intelligence. Meta (Facebook), OpenAI's principal rival, proclaims that the Singularity—the moment machines surpass human intelligence—is imminent. Meta races toward "Artificial General Intelligence"; OpenAI aims for "Artificial General Recognition.”

We have been heading this way for a long time. While the Luddites—working-class rebels—resisted from below, in 1863, Victorian essayist and satirist Samuel Butler, writing from within the establishment elite, warned that machines were evolving faster than humans and might supplant them. Since Butler, thinkers such as Nietzsche, Spengler, Heidegger, and historian and social critic Lewis Mumford have amplified the alarm.

With exceptional clarity, Jacques Ellul—a modern French philosopher and sociologist of technology—argued in The Technological Society (1954) that “technique” had become an autonomous force, evolving independently of ethics: what can be done, will be done. Efficiency becomes the highest value, narrowing freedom to technical choices. For Ellul, technology doesn’t merely change society—it defines it.

He also contended that this shift entails the elevation of image over word, spectacle over meaning. Images offer immediacy; words require interpretation. The word invites thought. The image overwhelms it. Memes compete, turning ideas into signals. Ellul would not be surprised that, in the age of Meta, even Jesus has become an avatar.

In The Humiliation of the Word, he warned that when the word is silenced, we lose nuance, contradiction, and moral depth. What we see stands in for what is. A ruthless, trolling politics, calibrated for social media, is coming for the rest of us. As the saying goes: "Who are you going to believe, me or your lying eyes?"

The word creates space between stimulus and response, allowing reflection, responsibility, and resistance. In a world curated by algorithms, The Humiliation of the Word reminds us that preserving the word is essential to preserving what remains human.

Before the Scientific Revolution, expression was assumed to emerge from a coherent self, grounded in tradition and moral imagination. Meaning was embedded in shared language. That coherence is fractured. In the age of AI, authorship and accountability are increasingly elusive. Expression may no longer come from someone who stood behind it.

Ellul's warning is urgent: when the dominance of the visible over the sayable becomes near-total—when appearances dictate meaning—the word, and with it the human voice, stand in danger of erasure; facts become optics. A tragic scene or a crying child goes viral, swaying millions, while the full context—let alone the truth—never trends. Even war becomes spectacle, religion performance, and daily life an advertisement.

But Ellul's vision was not merely a lament. To "save the word" is to recover the slow, dialogical practice of meaning-making: to speak, listen, question, interpret, and resist the flattening of experience into data.

The goal is not to halt AI, but to ensure that the word endures—amid the noise of algorithm and image—as a space for reflection, for responsibility, and as a defense of human dignity. The word holds what no algorithm can fake or replace: a story read aloud to a child, a note slipped into a lunchbox, a conversation that lingers, a book read in full—on paper or screen.

Hope, then, is not optimism. It is the stubborn act of keeping the word alive—so that even in a world reshaped by machines, we remain capable of meaning, freedom, and genuine encounter.

Long after the eye scan confirms identity, it’s the word that proves we exist. The Orb may certify that we’re human. The Singularity may loom. But no machine can ask what our voice does: What matters?

Notes and reading

Fractal eyes – Sam Altman's digital—and fundraising—genius is fractal: innovation hesitates; scaling doesn't. Fractal growth accelerates by expanding what already exists. The main bottleneck is capital—overcome by a record of success. Altman is "simply" building on the logic of AI. (Tip for writer's block: don't wait for a new idea—go fractal. Rework an old one.) — Karen Hao, Empire of AI (2025).

“Fractal” is my term for the self-reinforcing scaling strategy Hao describes.

“DOGE, Palantir and the IRS: What Could Go Wrong?” - CPA/Trendlines (July 10, 2025).

Early warning – In “Darwin among the Machines” (1863), reprinted in The Note-Books of Samuel Butler (2011), the Victorian satirist and iconoclast speculated that machines evolve through natural selection. They could eventually surpass and supplant humanity—not by revolt, but by out-adapting us.

Dawn – Octavia Butler (2011), science fiction. Lilith Iyapo wakes in a future remade by the alien Oankali, who saved humanity—at a price. To survive, humans must adapt to their ways, risking genetic “purity” for a future built on exchange. Chosen to lead, Lilith is caught between distrust on both sides. She doesn’t yield but learns and acts, shaping what follows. Lilith’s dilemma remains unresolved—like our own with AI. The future may depend less on purity than on learning to live with what is unlike us—not cyborgian. Simply wise.

The Technological Society and Humiliation of the Word, Jacques Ellul (1952-1954; 1985). Also, "Confronting the Technological Society - On Jacques Ellul's analysis of technique" - Collected essays edited by Samuel Matlack, managing editor of The New Atlantis (Summer/Fall 2014).

The Line: AI and the Future of Personhood - James Boyle, law and tech scholar (2024). Boyle urges clear legal standards for AI rights and duties—before courts or corporations improvise. Should a synthetic being testify, own property, or be liable? Don’t wait until a chatbot is sued or a robot demands asylum. Personhood has become a shifting boundary—one that law, culture, and technology redraw with each new case.

"I Let Sam Altman Scan My Eyeballs With His Glowing, Dystopian Orb" - Thomas Smith, Medium (June 22, 2025). Smith is an award-winning AI expert with 14 years of experience.

deeper and deeper into mirrors and smoke

Yes, there it is: "The word creates space between stimulus and response, allowing reflection, responsibility, and resistance." In Peircian terms, perhaps, the word creates the space of mediation between the sign and the signified. Images in words' place become something like a political state of emergency; a deliberative body gives way to an execution (a response) by an "executive."

And this in your response to Addison's comment: "You stay in it, not to win, but to witness." Yes! Witness speaks of both hearing/seeing and testifying, of mediating between what was witnessed and the community the witness serves. Without this "witness," all that remains is what you aptly describe as "spectacle over meaning."

(By the way, I've been enjoying Boym's The Future of Nostalgia, which you recommended in a previous post. This post may be going in the opposite direction--A History of Futurism?)