Tip-Off #208 - The Burnout Gospel

Positive thinking is the art of turning away from the truth and calling it courage.

A striking connection exists between conspiracy fears and the American dream of greatness. The nation’s grandiosity seems to require a hidden enemy for confirmation. This messianic logic shapes American politics—and remains central to much conservative evangelical Christianity. Ukraine wants peace. Russia wants an empire. We just want to be great.

In 1952, Norman Vincent Peale published The Power of Positive Thinking, which sold more copies in the U.S. than any nonfiction title except the Bible—a cherished gift from my Presbyterian father. Another Presbyterian father, Fred Trump, became a member of Peale’s Marble Collegiate Church in New York City. His son, Donald, later praised Peale’s influence: “My father was friends with Dr. Peale, and I had read his famous book. That helped. I’m a cautious optimist but also a firm believer in the power of being positive. I refused to be sucked into negative thinking on any level. Defeat is not in my vocabulary. That was a good lesson because I emerged on a very victorious level. It’s a good way to go.”

Negativity has no place. Exaggeration becomes truth—what Trump calls "truthful hyperbole… My brand.” (1987) Everything is the "biggest," the "best," the "greatest," the "smartest," the "richest."

This mindset, rooted in 19th-century "New Thought” movements, doesn't just ignore problems—climate change, inequality, racism, nationalism—it suggests problems exist because many are, per Trump, "losers."

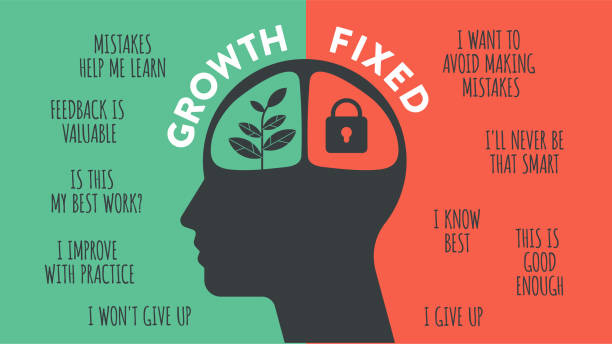

Democracy is messy. Authoritarian regimes promise to clean things up. Positive thinking can be a form of perfectionism. It often masks aggression and enforces narrow ideals of flourishing, recasting adversity as personal failure. Burnout becomes a badge of honor, proof of relentless “growth.” Exhaustion is rebranded as virtue; despair, a lack of will. “It’s always darkest before the dawn.” Encouragement turns coercive when the only acceptable response is a cheerful slogan. Even collapse must smile.

This logic finds a natural home in the wellness industry, where self-care has become a marketplace of compliance. Mood must be managed; doubt reframed as motivation. LinkedIn celebrates “grinding through the pain.” Speakers monetize their breakdowns. Instagram overflows with yoga poses and gratitude journals—behind the calm lies curated performance. Healing is a hustle.

You're the CEO of your happiness, responsible for optimizing your emotional portfolio. Corporate thinking seeps into private corners—feelings become metrics, relationships opportunities.

Take inequality. Instead of addressing wage stagnation or housing costs, we're told to focus on resilience. The unemployed must "network." The overworked, be grateful. It's not a mistake—it's a tactic: deflect reform, blame the sufferer. And why stop at blaming the victim? We can make gravity responsible for every fall.

This is domination by performance. Control doesn't come through constraint but through the demand to improve, enjoy, and produce. Self-improvement becomes a duty. Compulsion becomes pressure. People monitor themselves pursuing productivity.

The result is a society appearing free but riddled with fatigue, anxiety, and isolation. A new tyranny rules through the promise of fulfillment. It's harder to resist because it looks like care, harder to name because it sounds like freedom.

The compulsion shows in our language. We're not tired—we're "optimizing energy." We're not sad—we're "working through stuff." Pain must be aspirational. "Failure is not an option!" (Apollo 13—a "successful disaster"). A cynic joked, "Try harder. Fail better." W.C. Fields was probably right: "Try, try, try again. Then quit. No use being a damned fool about it."

Nobel Poet Wisława Szymborska, who lived through Nazi occupation and Communist rule, understood a different kind of hope. She found courage not in rallies and slogans but in attention to a blade of grass, a bad joke, the fact that people still fall in love.

For Szymborska, hope’s courage is in quiet affirmations of life’s value, especially when in doubt. It is durable and subversive: seeing without turning away, acknowledging pain without making it productive, finding meaning in gestures rather than narratives. "You can find the entire cosmos lurking in the least remarkable objects." We must have the stubbornness to look again at what is right before us.

In the same spirit, another poet who admired Szymborska wrote, “We can do without pleasure, but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless furnace of this world. To make injustice the only measure of our attention is to praise the Devil. We must admit there will be music despite everything.”

Perhaps this is what lies beyond burnout: not the gospel of performance, but the modern heresy of being human.

Notes and reading

New Thought, a 19th-century American spiritual movement, was the immediate predecessor of Peale’s “positive thinking.” Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866), a folk healer and mesmerist, is often credited as its founder. Mary Baker Eddy, who went on to found Christian Science, was once close to him—though she denied the connection.

“Positive thinking entered the mainstream of American life, reshaping how the nation understands itself—psychologically, religiously, commercially, and politically; the people behind it wrote the backstory of modern America.” (emphasis added)

- from One Simple Idea: How the Lessons of Positive Thinking Can Transform Your Life (2016) by Mitch Horowitz, historian of alternative spirituality. “One of today’s most literate voices of esoterica, mysticism, and the occult.” The Washington Post.

Bright-sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America - Barbara Ehrenreich (2010). Ehrenreich was an award-winning columnist and essayist who addressed a range of themes, including the myth of the American Dream, the labor market, healthcare, poverty, and women’s rights.

The Power of Positive Thinking - Norman Vincent Peale (1952). - “You gave me great strength during the most difficult time in my life.”—Richard Nixon, in a personal letter to Peale after Watergate. “Dr. Peale shows great spiritual truths to be simple rather than complex.”—Ronald Reagan during the Presidential Medal of Freedom ceremony honoring Peale.

Surge of Piety: Norman Vincent Peale and the Remaking of American Religious Life - Christopher Lane (2016). Lane is a member of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities at Northwestern's Feinberg School of Medicine. Authored The Age of Doubt: Tracing the Roots of Our Religious Uncertainty.

Donald Trump - The Art of the Deal (1987) - #1 on The New York Times Best Seller list for a year. Tony Schwartz, American journalist, ghostwriter. “But they’re my ideas” - Trump. (“Why did you ask a million dollars for that house? You know it isn’t worth that much.” “I should have asked for two million.” - Not word-for-word from The Art of the Deal, but it might as well be.)

Wislawa Szymborska - Nobel Lecture 1996, “The Poet and the World.” - “You can find the entire cosmos…” in a Publishers Weekly interview, “Wislawa Szymborska: The Enchantment of Everyday Objects” (Academia.edu - April 7, 1997).

“Nobelist Wisława Szymborska on ‘work as one continuous adventure’” - Cynthia Haven, The Book Haven (blog - October 24, 2014). Haven is a literary scholar, author, critic, Slavicist, and journalist, best known for her biography Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (2018).

“We can do without pleasure, but not delight…” - from Jack Gilbert’s poem “A Brief for the Defense” (Refusing Heaven, 2005). Gilbert, the reclusive American poet known for his emotionally direct verse, revered Szymborska for her wit, irony, and deceptive simplicity.

Tip-Off #207 - Not with a Beast but a Spreadsheet

forthcoming #209 - Authorship and the Ancient Debate