Meaning Without Illusion

When meaning dies, creation waits to speak again.

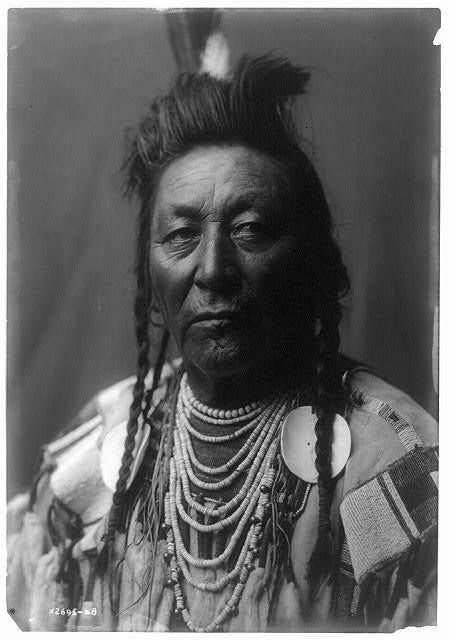

Jonathan Lear, who died in September in Hyde Park, Chicago, was more than a celebrated philosopher. Defying academic convention, he took a hands-on approach to thought, visiting the Crow Nation to study resilience and training as a psychoanalyst to explore Freud. Idiosyncratic and playful, he brought ancient Greek thinkers into dialogue with modern theory to probe irony, love, hope, and human finitude. Radical Hope (2006) remains his most arresting book, asking what happens when a world ends—not the planet, but a people’s world of meaning.

Lear begins with a haunting remark from Plenty Coups, the last traditional chief of the Crow Nation, spoken near the end of his life in 1932:

“When the buffalo went away, the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this, nothing happened.”

Nothing happened—because nothing made sense outside that way of life. When the buffalo vanished and war ended, the Crow world collapsed. The actions that once defined a good life lost meaning. Courage, honor, and purpose no longer had an end—their reason for being.

Lear reconstructs the Crow ethos: hunting and warfare as paths to honor. To “count coups”—public acts of bravery—was to plant one’s stake and stand firm. When war and buffalo were gone, such deeds became impossible, and the noble became unintelligible.

Through his dream of the Chickadee—the Crow’s bird of listening and learned survival—Plenty Coups turned a traditional symbol into a creative response to crisis, offering his people a path forward rooted in heritage. Chickadee virtue demanded a new kind of courage, yet drew its strength from the old.

Lear calls this radical hope: courage to imagine a future good beyond understanding. It is not optimism or faith in progress, but a moral act of imagination—a refusal of despair when even words for hope have disappeared.

Today, one cannot be a Crow in the old sense. And yet the Crow survives—teaching its language, preserving songs and stories. But Plenty Coups envisioned a deeper form of survival —a renewed flourishing beyond mere endurance. As witness to the death of traditional Crow life, he could not yet say what that future would be.

Still, on the strength of his dream, he staked everything on its renewal—beyond the abyss. It is hope that endures the death of meaning, listening as confidently as his ancestors. That was Plenty Coups’s courage.

For Lear, renewal begins with courage transformed. When the old battlefield vanishes, the virtue must be redefined. The Crow warrior’s courage—valor bound to war—gives way to steady action amid uncertainty: bravery when its meaning is unclear. The old rules aren’t broken; they no longer apply.

Lear’s insight reaches beyond the Crow: every society faces moments when the forms that held it together give way—when courage and duty lose their bearings. We imagine ourselves adaptable, yet that confidence conceals a deeper unease: our sense of meaning coming apart.

Our faith in flexibility has become its own rigidity—we adapt to everything except the loss of meaning itself. Factories close, towns empty, professions vanish, and the honor once tied to work or craft dissolves with them. We face Plenty Coups’s question: how to live when the world that made sense no longer does.

Radical hope begins with listening—like the Chickadee, alert to new signals—and depends not on nostalgia but imagination. It means acting faithfully without knowing the outcome. It demands a different kind of courage than battlefield heroism: to move forward under uncertainty, to recreate meaning without illusion.

The source of such hope remains unnamed. Lear describes it but leaves its origin open. Who serves best doesn’t always understand. That may be the point. Radical hope does not rely on doctrine or prediction. It trusts that meaning can return, even if we cannot picture its shape.

Tradition’s call is not just “Repeat what we said” but “Do as we have done.” With feet in the present, we look and listen for the truth our ancestors knew, grasping it in terms of our time. Truth does not change, but our relation to it does. It takes shape from the moment it inhabits—and reshapes that moment from within. Rightly understood, tradition looks forward; that was its purpose from the beginning.

The world Lear described is not lost to history; it surrounds us still. The rituals that once grounded us—work, worship, learning, conversation—are thinning out, like air at altitude. We scroll instead of speak, measure instead of mean.

Yet the possibility Lear named remains. Radical hope is not optimism but perseverance with imagination: the courage to live as if meaning still matters, even when it falls silent. Out of that silence, something new begins to speak.

To honor the past is to keep it unfinished. Tradition endures as it began—by looking forward.

This reflection is written in remembrance of Jonathan Lear (1948–2025), widely regarded as one of the most original moral philosophers of his generation.

Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation (2006).

Control on crazy dreams: For the Crow, a dream became a guiding vision when a powerful helper—like the Chickadee-person—appeared in it, and elders publicly interpreted its meaning.

In 1921, at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier’s dedication, Plenty Coups represented the Plains Indians and laid his war bonnet and coup stick on the tomb—honoring the Crow Nation and all who fell.

“From Warrior to Statesman: The Leadership of Chief Plenty Coups”—Center of the West (August 27, 2025).

Notes and reading

“A Different Kind of Courage” — Charles Taylor, The New York Review (April 26, 2007). “Drawing on the Crow Nation, Jonathan Lear offers insight essential to rebuilding a moral world.” Taylor is a Canadian philosopher and professor emeritus at McGill University.

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (2012) — Nassim Nicholas Taleb, essayist-statistician and former options trader behind Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan. Taleb argues that some systems don’t just survive shocks; they grow stronger—a secular analogue to Crow courage.

Henry Oliver—Second Act (2024). Case-driven portraits showing how earlier training, mentors, and inherited forms can be repurposed for a new future—tradition as toolkit rather than shrine; Oliver is a writer-critic and Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University.

“Who serves best doesn’t always understand.”—from poem “Love,” Czesław Miłosz, Polish-American poet who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980.

Cf. “You pray to God it actually means something. But the meaning is a secondary next step from original creation.” — Rock legend Nick Cave about his music. The Free Press (October 30, 2025), further in his newsletter The Red Hand Files, a personal response to reader questions.

For wider reading related to this reflection:

David Bentley Hart — The Experience of God (2013); The Beauty of the Infinite (2004). Reads the collapse of meaning as a summons to receptivity—attunement rather than reinvention—complementing Lear by grounding radical hope in responsiveness to the intelligence underlying all being. Hart is one of the most formidable Christian intellectuals of our time.

This reflection on tradition and hope in the face of the loss of a people’s world of meaning gets, I believe, to a large part of our work today. How do we reach back when the context of anything we could put our hands on is gone?

The dilemma reminds me of Romeo’s lines at the outset of Act 2, right after he learns that his suddenly promising new world—Juliet’s home—has just as suddenly become a death trap:

“Can I go forward when my heart is here?

Turn back, dull earth, and find thy center out."

How can we just run, or only run? His struggle to find a center reminds me of some Native American nations’ migrations, their search for their homes at the earth’s center.

I wasn’t aware of Radical Hope, and I look forward to reading it (as well as Antifragile and The Experience of God). I’ve been reading what I think is something similar: Damian Costello’s Black Elk: Colonialism And Lakota Catholicism. In it, Costello quotes O. Douglas Schwartz on the role of a holy man at the end of a known world:

“The holy man has a ‘vision’ of the world—its nature, its history and its destiny—and a sense of humanity’s place within that scheme. Through that vision, the holy man can hope to solve problems for which the tradition offers no ready-made solutions. The wicasa wakan is then the theoretician—the theologian—of the Plains religion.”

Your post also reminds me of Albert Schweitzer's understanding of mysticism. His version of Paul, who leads the church out of the senselessness of Jesus’ delayed parousia, seems similar to Costello’s Black Elk and Jonathan Lear’s Plenty Coups. Eric Voegelin’s concept of the philosopher (in Anamensis) comes to mind as well: someone who can show a community how to return to the ground of being when the foundations of common sense crumble.

You offer so much stunning language here— substantive, articulate, and hopeful (in the face of our culture’s increasingly mute and gabby despair). Just a sample of what I enjoy:

“Radical hope is not optimism but perseverance with imagination: the courage to live as if meaning still matters, even when it falls silent. Out of that silence, something new begins to speak.”

Thank you for this work.