Called by Name

“At his gate lay a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores.” — Luke 16:20

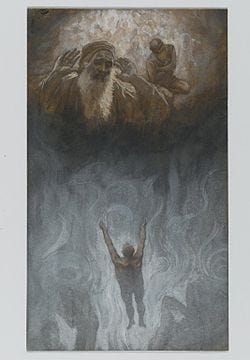

Two men die the same night. One is rich, dressed in purple. The other is Lazarus, a beggar whose sores are licked by dogs. Death reverses their fortunes: the beggar is carried to Abraham’s side; the rich man descends into torment.

Across a fixed chasm, the rich man begs for a drop of water, then for someone to warn his brothers. Abraham answers with finality: if they will not listen to Moses and the prophets, not even a man returned from the dead will change their minds.

Lazarus is the only person named in Jesus’ parables. Others—the good Samaritan, the Pharisee, the father, the older son—remain anonymous. He was not a farmer in drought or a woman searching for a coin. He was a human ignored at the gate, his name meaning “God helps,” his presence an accusation.

Parables defy neat definition. They lure us toward an answer, then a trapdoor opens, and we fall to a deeper mystery. Humorist Calvin Trillin said he flunked tests because his teachers couldn’t understand that many of his answers were meant ironically. The disciples kept asking why Jesus spoke that way. Jesus couldn’t fool the authorities, who understood what he was saying and executed him as a political subversive.

We often tell the parable as a morality play: the rich are damned, the poor saved. But Jesus’ story is stranger and sharper. It does not canonize poverty or demonize wealth; it exposes the blindness comfort breeds. The rich man could see Lazarus—covered with sores and starving—at his gate, yet chose not to care, or only to feel guilty. His sin was not ignorance but inertia.

As Max Weber observed in his essay “The Social Psychology of World Religions,” the endurance of such blindness owes less to logic than to psychological need. “The fortunate man is seldom satisfied with the fact of being fortunate,” he wrote. “He needs to know that he has a right to his good fortune… that he deserves it, and above all that he deserves it in comparison with others. Good fortune thus wants to be legitimate fortune.”

The reversal after death was not punishment but truth made visible. Robert Frost said, “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall”—yet somehow keeps the gate closed. Each of us stands near that gate. Sometimes we cross it without noticing, or build it higher.

The story endures because it leaves no one out. Poverty and wealth are matters of recognition and compassion, not only of politics. The rich can be saved—“Nothing is impossible for God.” The poor can be lost when pain turns love to ash.

No one has a monopoly on virtue or vice. In the end, everyone is judged by love—“for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous.” Grace is free for all, but not cheap. It burns like a refiner’s fire, consuming every denial of love until only love remains.

Stocks hit records this week. Yet the optimism is confined to a few. The market’s joy is a thin veneer over conflict, inflation, AI-induced job losses, and poverty—a system creating record wealth and precarity at once.

What can we do in the face of such injustice? The rich man’s sin was not wealth or greed but inertia—the paralysis of indifference posing as comfort. Justice is not just a cause, not just politics and a plan, or prison reform and fair housing. It is a cup of cold water and a visit to an inmate.

We live by more than bread—but we do live by bread. Loving our “neighbor” became abstract—systemic—more important than the one next door. It’s urgent to press for humane food laws, but no more so than bringing Thanksgiving dinner to a family living on hot dogs and potato chips.

Jesus told another story—of being hungry and fed, thirsty and given a drink—and said, “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” His parables were never about issues; they were about people, where justice begins.

We need no miracle to know the poor are with us, nor threats of torment to be moved. If we cannot see the person at our gate—on the street, in the appeals that cross our screens—we are already lost.

What the rich man asked Lazarus to do—to warn his brothers—the parable itself does for its readers. The question lingers: would the brothers heed the prophets’ call to love the neighbor and the stranger? We do not know.

Will we? For those who listen, the call is already here—to see, to answer, to be called by name exactly where we are.

Notes and reading

“The Rich Man and Lazarus” — Luke 16:19–31

Scripture references: Matthew 5:45, Luke 18:27, cf. Luke 8:13, Matthew 25:31-46.

Parables of the Kingdom — C. H. Dodd (1961). Dodd was a prominent New Testament scholar best known for his idea of “realized eschatology”—the view that God’s kingdom is already at work in the present, “what God has done and is doing now in Christ.” Later scholars did not adopt Dodd’s framework uncritically, emphasizing instead that the gospel holds both the “now” and the “not yet.”

Short Stories by Jesus — Amy-Jill Levine (2014). A Jewish New Testament scholar, Levine reads the parables within their first-century Jewish context, stripping away sentimental or allegorical interpretations. She emphasizes their humor, provocation, and social edge—stories meant not to comfort but to challenge listeners to see differently.

Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, edited and translated by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (1946). “The Social Psychology of World Religions” is one of the major essays.

Robert Frost — “Mending Wall,” in North of Boston (1914). The line “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” opens the poem and reappears near its close, framing the speaker’s dialogue with his neighbor, who insists, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

I really think it's both. I have to watch out for turning parables into proverbs. I think irony and ambiguity are less "the point" than true to life and a need to think twice before jumping to a point. - Thanks for your comment!

Sometimes the memory of Jesus’s Rich Man and Lazarus surfaces like the faces of the distant poor on my TV or on the envelopes of charities’ mass mailings. But the poor are “with us,” as Jesus said, and are like the advancing cars in my side-view mirror—closer than they appear. Like the parable's rich man, I pass the poor every day. Thank you for presenting this parable in the context of a fresh take, at once balanced and challenging. My cutting a few checks to some of the world’s Lazaruses won’t make this parable go away.

Some specific thoughts on two of your points:

“Lazarus is the only person named in Jesus’ parables. . . . He was a human ignored at the gate, his name meaning “God helps,” his presence an accusation.” History usually remembers the names of the rich and powerful. In Jesus’s parable, now that you mention it, Jesus reverses this historical tendency.

“We often tell the parable as a morality play: the rich are damned, the poor saved. But Jesus’ story is stranger and sharper. It does not canonize poverty or demonize wealth; it exposes the blindness comfort breeds.” While visiting one of our daughters, we’re taking a “rich man’s” tour of middle California. Tour buses and the landscapes they choose to travel are like what you describe as “the market’s veneer”: they often present a curated version of an area to prop up the rich’s worldview and to protect our sensibilities. I have enough money to remain blind, and I often spend it for that purpose, sometimes even when I give.

Two more lines I can’t put down:

“The rich man could see Lazarus—covered with sores and starving—at his gate, yet chose not to care, or only to feel guilty. His sin was not ignorance but inertia.”

“Loving our ‘neighbor’ became abstract—systemic—more important than the one next door.”

Side note: I wonder if Dodd’s emphasis on the “now” made room for some of his critics to emphasize (or even to simply include) the “now” with the “not yet.” I don’t know enough about theology to know.

Thank you again for presenting me with the gospel.